Introduction

Compilation vs Interpretation

You may have heard of the distinction, but what does it actually mean?

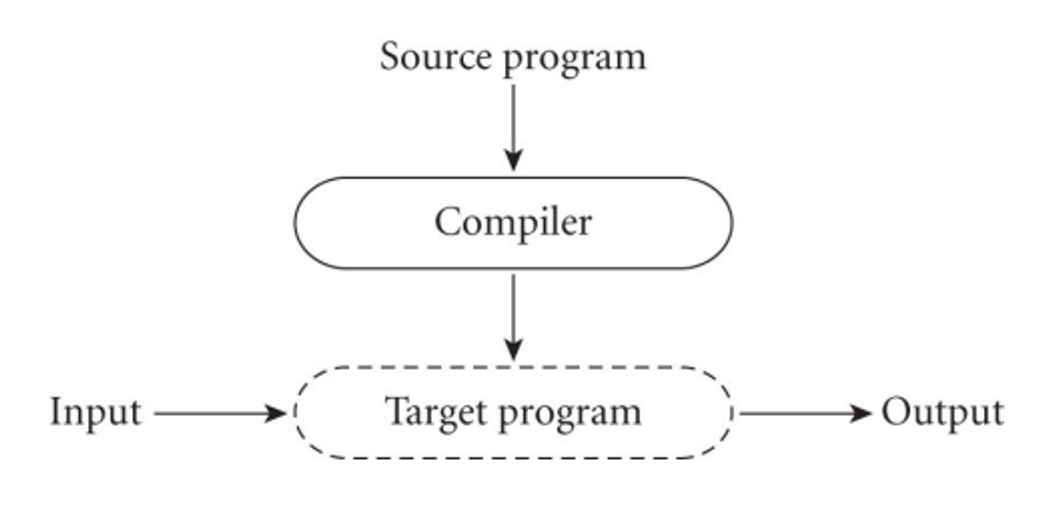

With a compiled language, we compile everything into bytecode before running anything

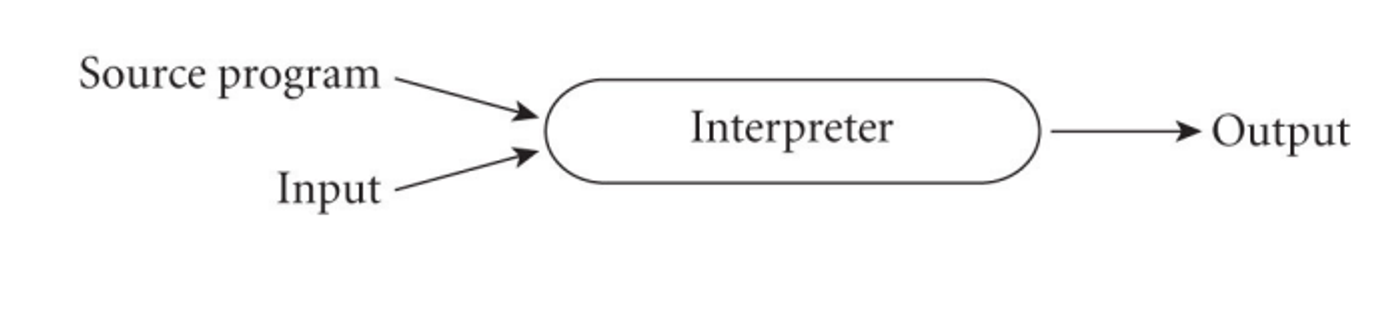

With interpreted languages on the other hand, we have an interpreter throughout the program’s runtime translating each instruction into bytecode as it goes along

With compilation, we get better performance since we don’t have the bloat of an interpreter, but interpretation gives us greater flexibility and better diagnostics

- For example, Prolog can write new pieces and execute them on the fly

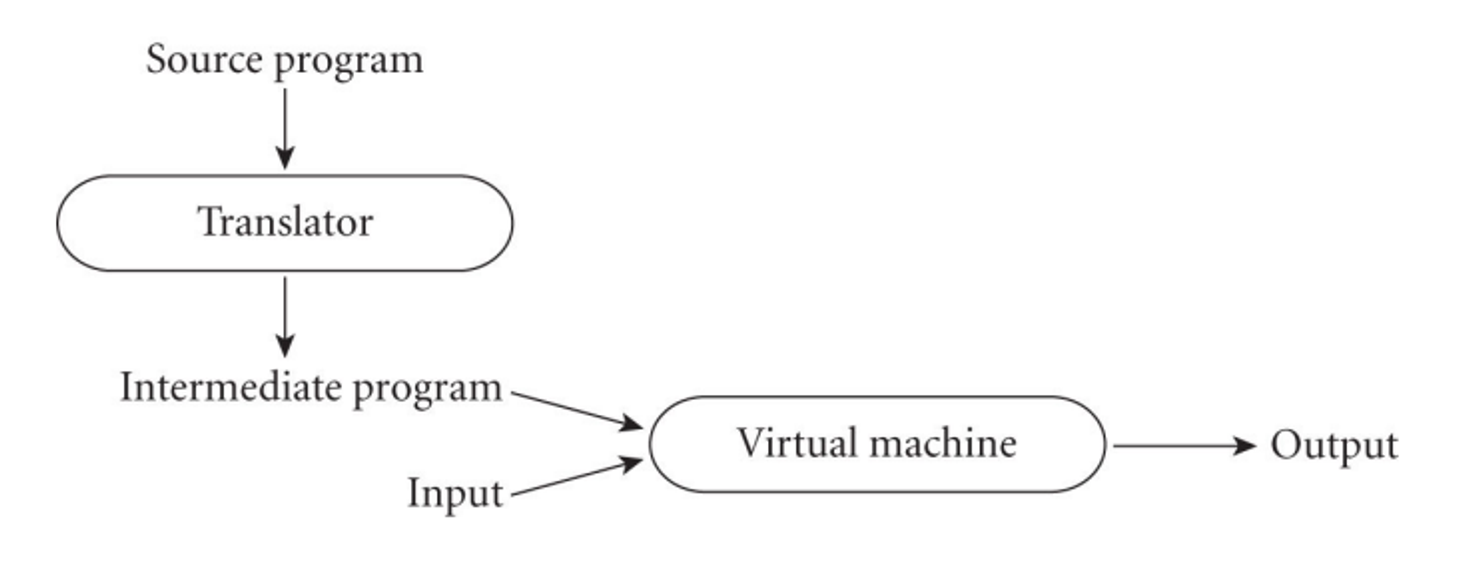

These aren’t mutually exclusive, however; you can have a system where we compile and then interpret

To put things more specifically, compilation is translation from one language into another, with full analysis of the meaning of the input

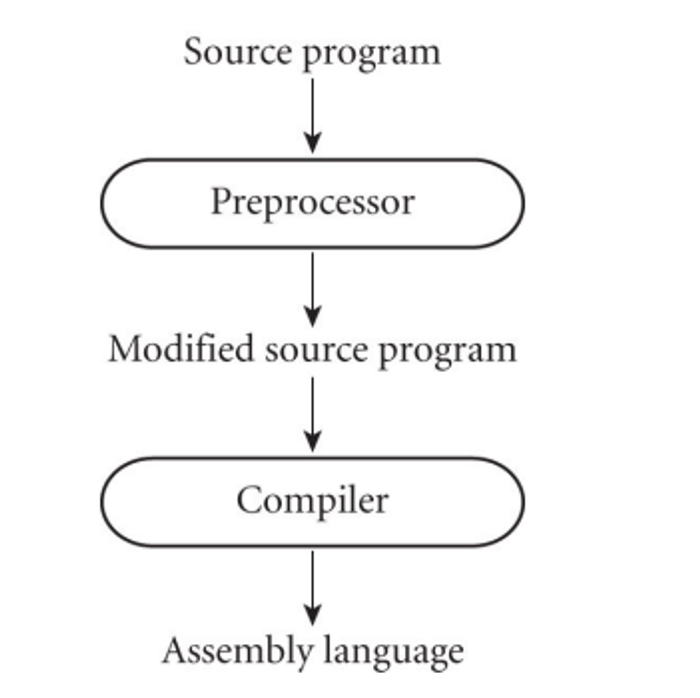

This entails semantic understanding of what is being processed, while pre-processing simply removes comments and white space while grouping characters into tokens, expanding abbreviations and maybe identifying loops or subroutines

- Preprocessors are more common for interpreted languages, but they also exist in C/C++

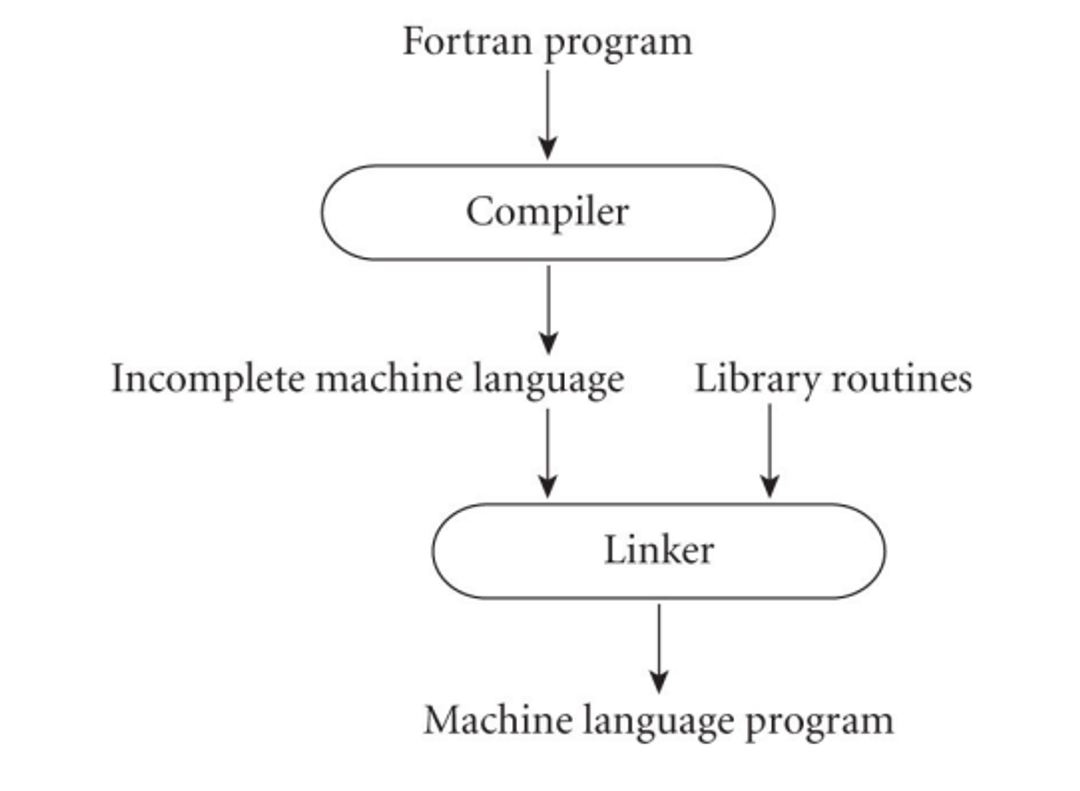

We can also use a linker to merge libraries of subroutines (ex. math functions like log) into the final program

We can also compile languages that are considered ‘interpreted’ since interpretation/compilation is actually a property of implementation

The compiler, in this case, will generate code that makes assumptions and runs very fast if the assumptions are valid

- If they aren’t valid, we can dynamically check with an interpreter

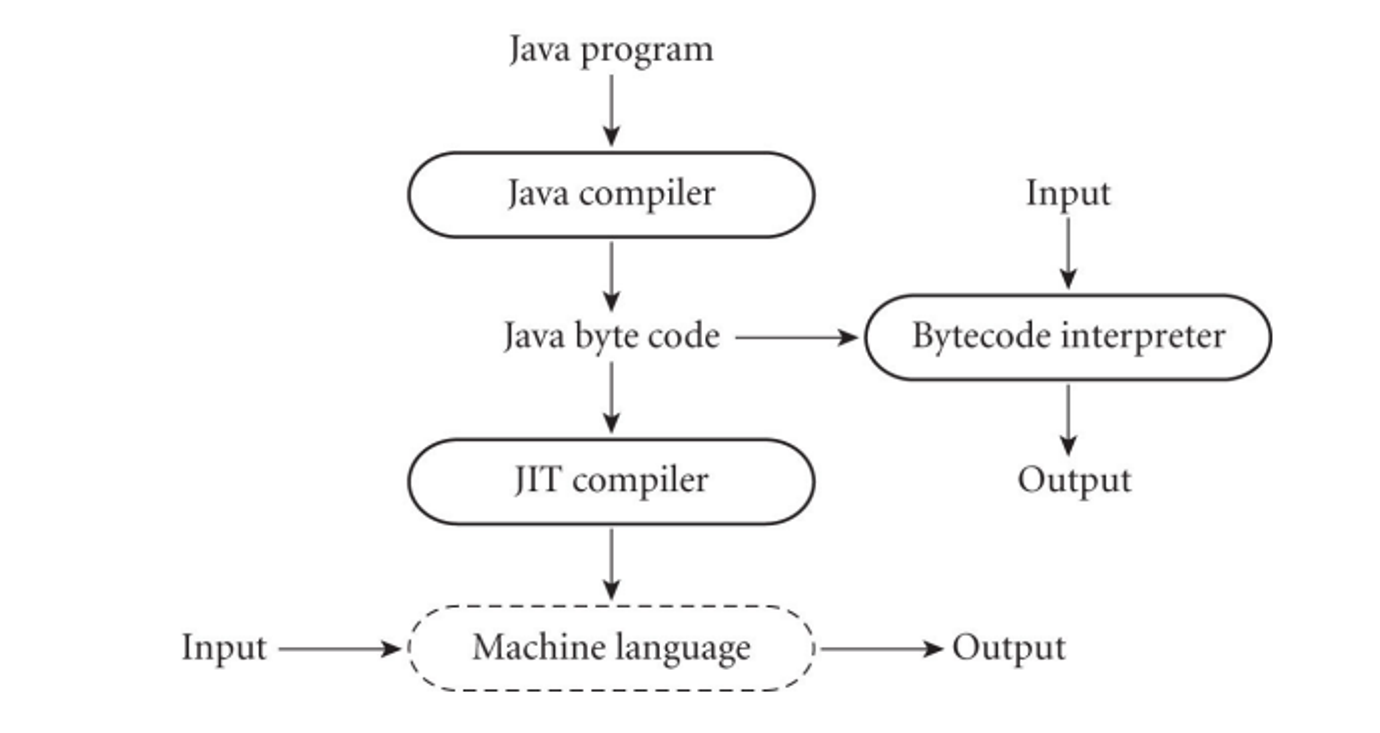

Another more modern way of approaching things is Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation, where we delay compilation until the last second

Some more unconventional compilers include text formatters that compile high-level document (Latex) and query language processors that translate into primitive operations on files (SQL)

- There’s also tools in IDEs that are separate from this, including debuggers, version management and profilers for performance analysis

Compilation/Interpretation Phases

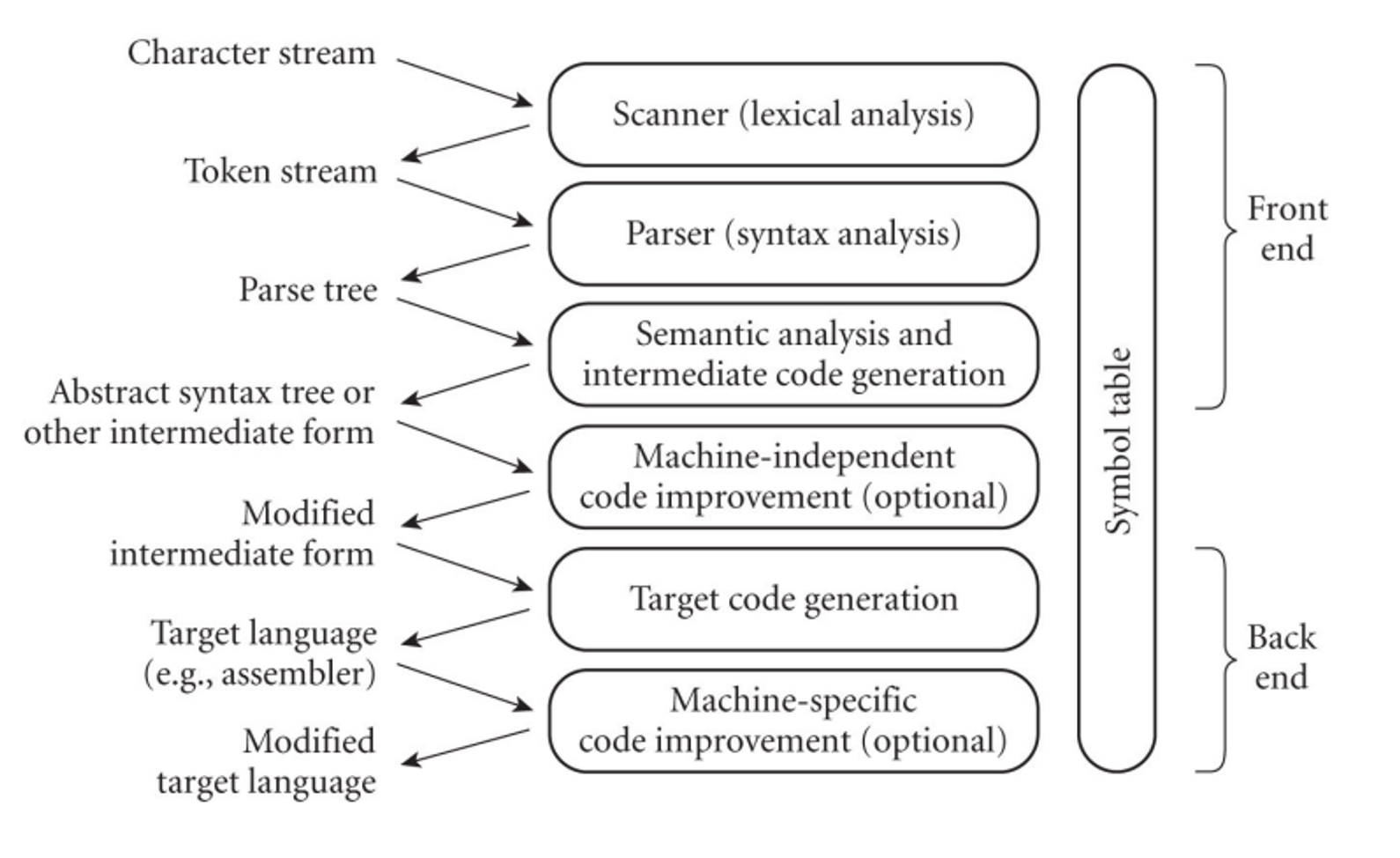

Compilation is handled in several steps

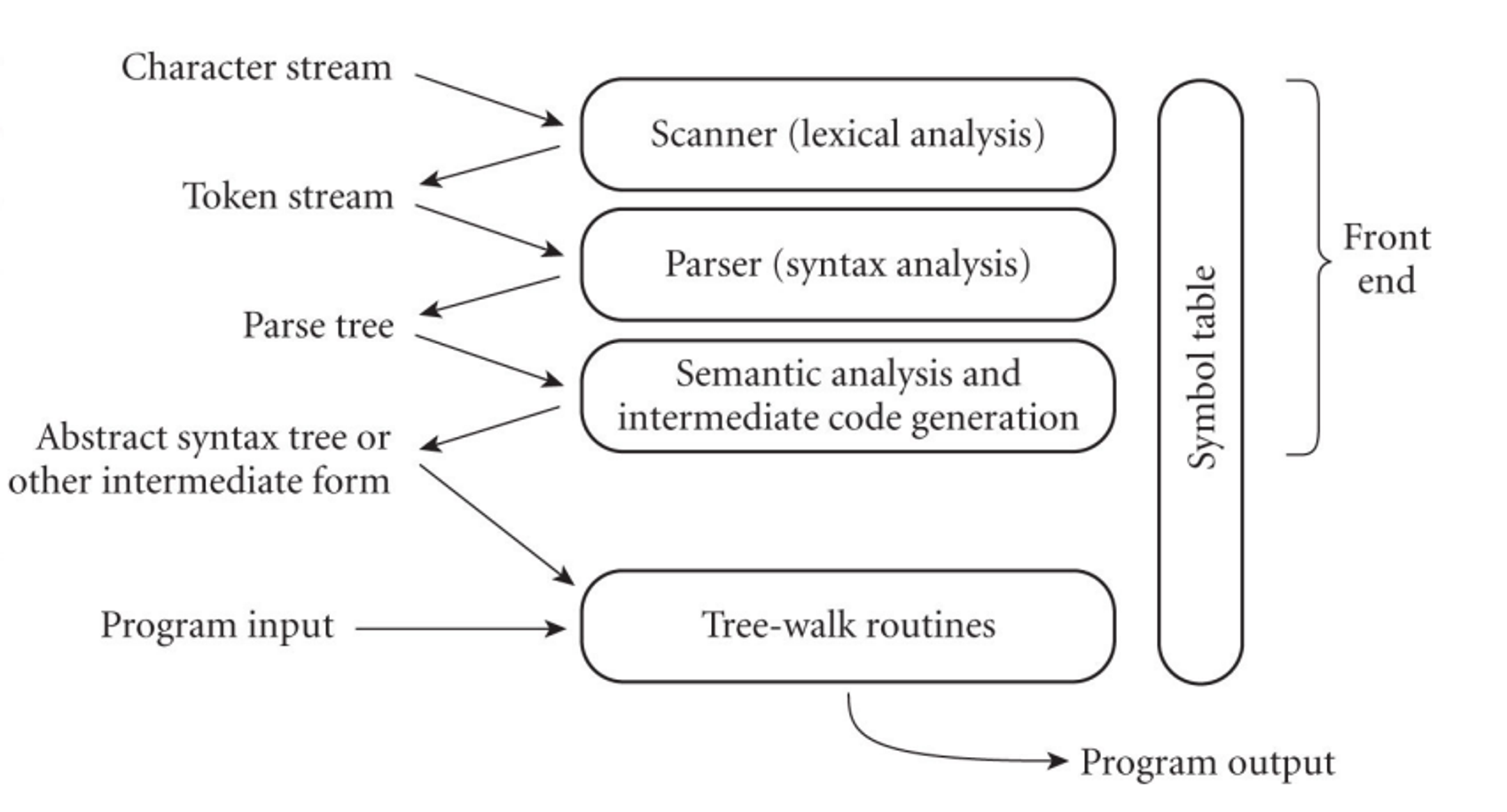

For interpretation, things are cut short a little bit

In the scanner, we divide the program into token, which are the smallest meaningful units, saving time since char-by-char is very slow

- This is done using a deterministic finite automata (DFA)

Scanning

C Program (computes GCD):

int main() {

int i = getint(), j = getint();

while (i != j) {

if (i > j) i = i - j;

else j = j - i;

}

putint(i);

}

Input – sequence of characters:

‘i’, ‘n’, ‘t’, ‘ ’, ‘m’, ‘a’, ‘i’, ‘n’, ‘(’, ‘)’ ...

Output – tokens:

int, main, (, ), {, int, i, =, getint, (, ), ,, j, =, getint, (, ), ;, while, (, i, !=, j, ), {, if, (, i, >, j, ), i, =, i, -, j, ;, else, j, =, j, -, i, ;, }, putint, (, i, ), ;, }

On parsing, we check the syntax of the program to make sure the grammar is being adhered to, which is done via a pushdown automata (PDA)

This parsing organizes tokens into a parse tree as defined by a context free grammar (CFG)

Parsing

Example – while loop in C

Context-free grammar (part of):

iteration-statement → while ( expression ) statement

statement → { block-item-list-opt }

block-item-list-opt → block-item-list | ε

block-item-list → block-item block-item-list → block-item-list block-item

block-item → declaration block-item → statement

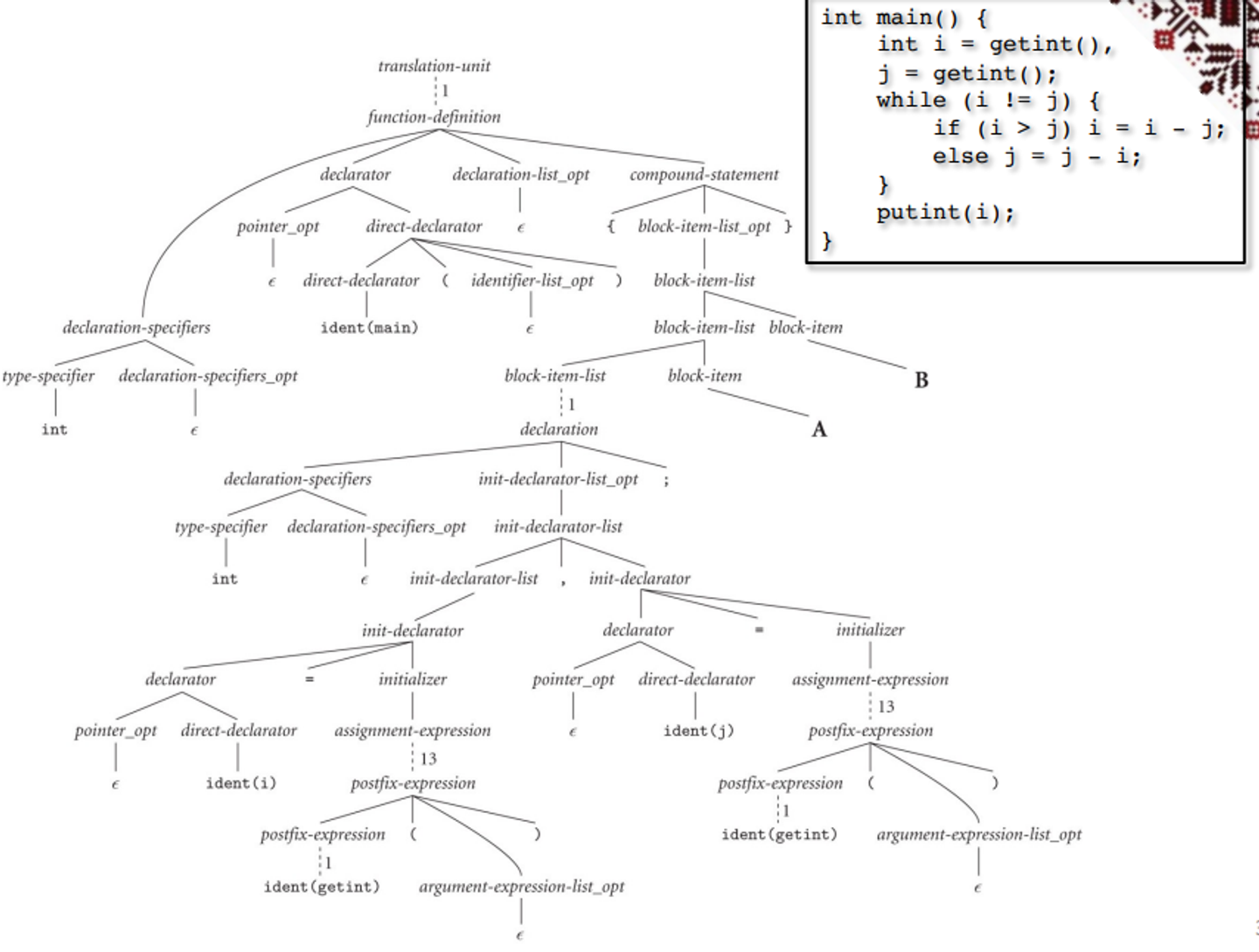

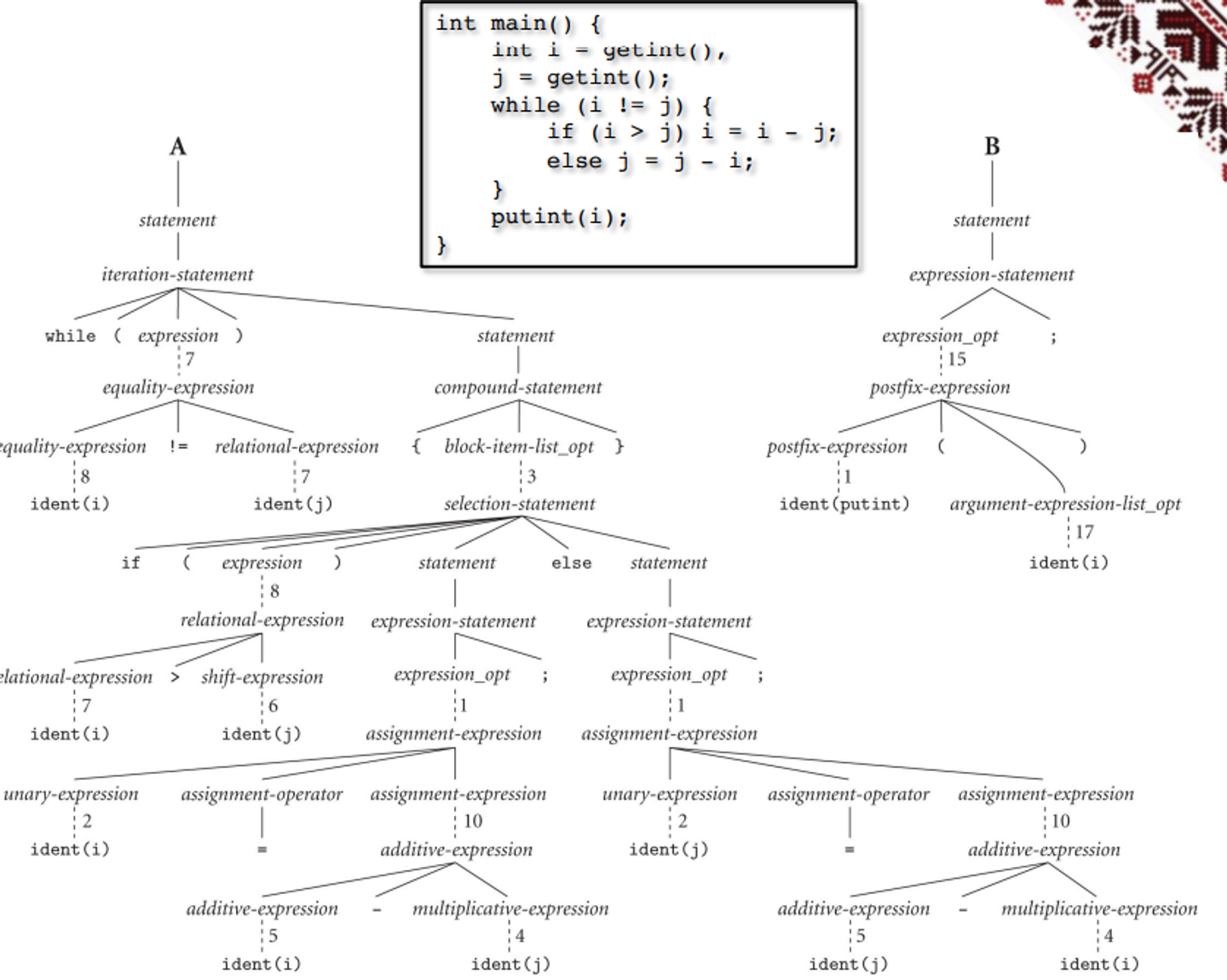

Parse tree for GCD program

- based on full context-free grammar

From here, our previous GCD example can be split up into a parse tree

- You can go through the leaves left-first to read out the entire program

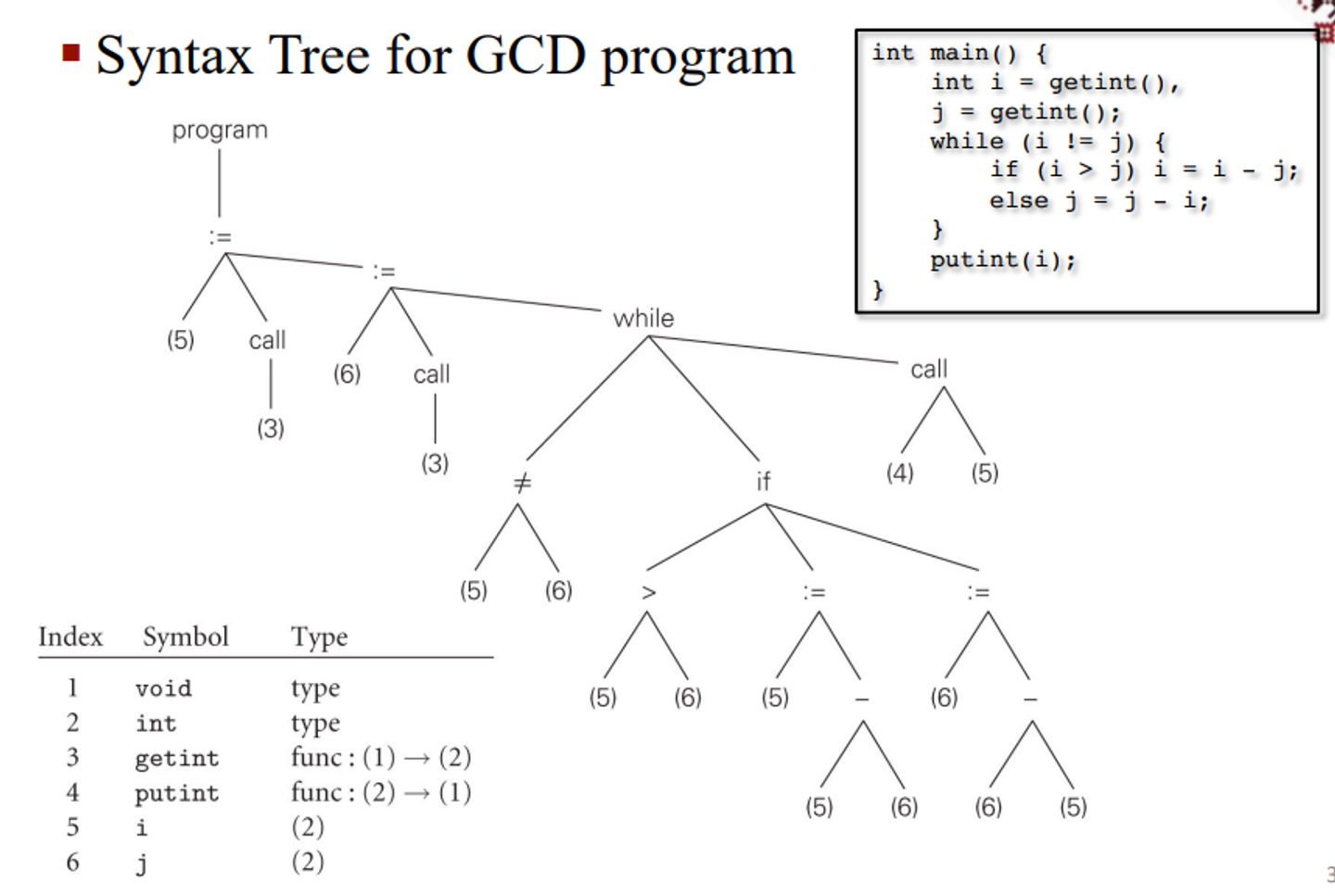

With semantic analysis, we discover the meaning in the program, detecting multiple occurrences of the same identifier and tracking the types of identifiers and expressions

From here, we can build and maintain a symbol table mapping each identifier to its information (type, scope, structure, etc.)

The compiler can only handle static semantic analysis, since dynamic semantics must be checked at run time

- These dynamic checks are pretty slow, so we need to make a trade off between safety and speed (this is what makes C so fast; dynamic checks are few and far in between)

This semantic analysis produces a syntax tree, removing some of the more “useless” internal nodes that are present in the parse tree and annotates the remaining nodes with attributes

Finally, we have code generation which uses interpreters to run the syntax tree and target code generation which then produces assembly

Assembly Code for GCD Program

pushl %ebp # \

movl %esp, %ebp # ) reserve space for local variables

subl $16, %esp # /

call getint # read

movl %eax, -8(%ebp) # store i

call getint # read

movl %eax, -12(%ebp) # store j

A:

movl -8(%ebp), %edi # load i

movl -12(%ebp), %ebx # load j

cmpl %ebx, %edi # compare

je D # jump if i == j

movl -8(%ebp), %edi # load i

movl -12(%ebp), %ebx # load j

cmpl %ebx, %edi # compare

jle B # jump if i < j

movl -8(%ebp), %edi # load i

movl -12(%ebp), %ebx # load j

subl %ebx, %edi # i = i - j

movl %edi, -8(%ebp) # store i

jmp C

B:

movl -12(%ebp), %edi # load j

movl -8(%ebp), %ebx # load i

subl %ebx, %edi # j = j - i

movl %edi, -12(%ebp) # store j

C:

jmp A

D:

movl -8(%ebp), %ebx # load i

push %ebx # push i (pass to putint)

call putint # write

addl $4, %esp # pop i

leave # deallocate space for local variables

mov $0, %eax # exit status for program

ret # return to operating system

Corresponding C Program:

int main() {

int i = getint(), j = getint();

while (i != j) {

if (i > j) i = i - j;

else j = j - i;

}

putint(i);

}

This is a bit of a naive solution that can definitely be approved upon, so our final step is to find these optimizations to either do things faster or take less space

Assembly Code Example

pushl %ebp

movl %esp, %ebp

pushl %ebx

subl $4, %esp

andl $-16, %esp

call getint

movl %eax, %ebx

call getint

cmpl %eax, %ebx

je C

A:

cmpl %eax, %ebx

jle D

subl %eax, %ebx

B:

cmpl %eax, %ebx

jne A

C:

movl %ebx, (%esp)

call putint

movl -4(%ebp), %ebx

leave

ret

D:

subl %ebx, %eax

jmp B